Where Will the Dung Go Without the Milky Way?

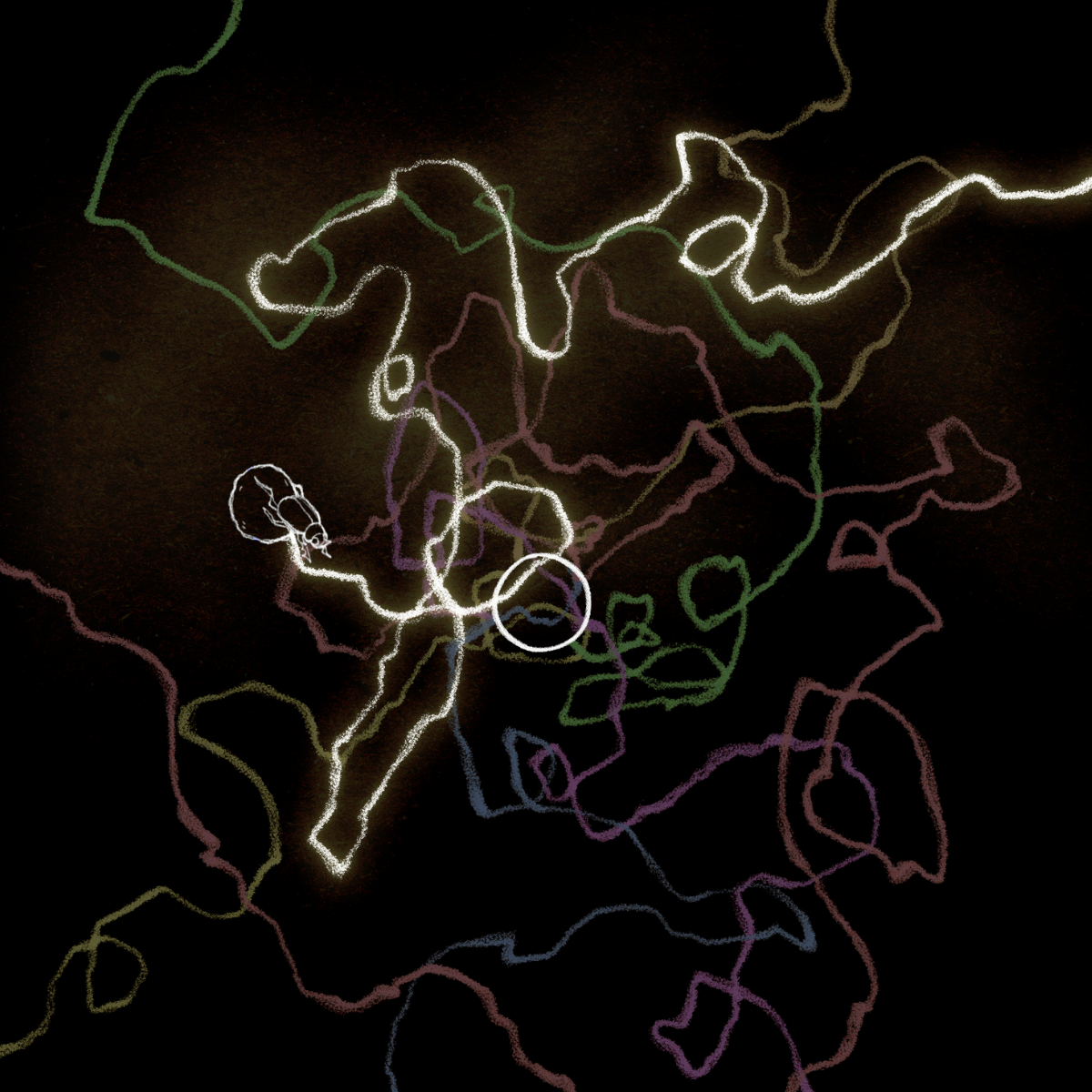

We stepped out of our human shoes by cosplaying as wildlife to rethink the presence of city lighting and how it shapes our sense of identity. Humans have long admired light, we build monuments to it, string it along streets, wrap it around towers, and scatter it into the sky to mark our triumph over darkness. For us, light is beauty, safety, culture, pride, and economy. But for other beings, light is simply life, or the disruption of it.

For the creatures who share this world, light is not art or status; it is a force that governs birth, hunting, sleeping, migrating, and surviving. One bright streetlamp can mean the difference between a successful hunt and starvation; an artificial skyline can mean the difference between a safe journey and disorientation.

Consider the remarkable dung beetle, nature’s tiny astronomer. This humble insect is the first known animal to use the Milky Way as a guiding map. These beetles do not care for our city’s neon signatures or our illuminated billboards. They don’t read maps, check GPS, or look for street signs. Their compass is written in the sky, stars scattered like breadcrumbs for the instinctive traveler.

Yet in our human pursuit to make the night as bright as day, we have smudged out their map. The stars fade behind the haze of urban glow; the Milky Way dissolves into our artificial dusk. The beetle’s simple, ancient task, to roll its dung ball in a straight line away from the competition, collapses when the sky is obscured.

A 2013 study demonstrated this beautifully: when guided by starlight, dung beetles push their dung balls in remarkably straight lines. When clouds or city glare hide the stars, their paths wobble. Researchers found that a beetle wearing a tiny light-blocking cap stumbles as though blindfolded. Offer it a mirror sun or an LED sun, and it accepts the illusion, doing its best to follow an imitation of the real thing.

In planetariums, dung beetles navigate beneath projected galaxies just as they would under the vast, authentic dome. They remind us that a beetle’s brain is not too small for stars, and our cities are not too big to erase them.

Today, one-third of humanity can no longer see the Milky Way. 60% of Europeans. 80% of Americans. What happens when these numbers apply not just to us, but to every creature whose instincts depend on this ancient map?

We build our cities brighter every year, but in doing so, we dim something essential, not only for beetles but for ourselves. We have lost touch with our own primal navigation. In our obsession with light, we neglect the darkness that once kept us humble, made us look up, made us wonder where we fit into a vast, star-speckled order.

Now we drift, no longer guided by Polaris, Orion, or the Milky Way, but by synthetic suns and digital stars. And in this navigating chaos, we collide with each other and with our own nature.

Where will the dung go without the Milky Way? A small question, but behind it, a larger one: Where will we go without the darkness that reveals the stars?

Perhaps it is time we remember that we, too, are animals under a sky we did not make. And maybe, just maybe, it’s not more light we need, but clearer darkness, and the courage to follow it back to something true.

References:

Dacke, Marie, et al. “Dung Beetles Use the Milky Way for Orientation.” Current Biology, vol. 23, no. 4, Feb. 2013, pp. 298–300. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2012.12.034.

Davis, Nicola. “Milky Way No Longer Visible to One Third of Humanity, Light Pollution Atlas Shows.” The Guardian, 10 June 2016. The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/science/2016/jun/10/milky-way-no-longer-visible-to-one-third-of-humanity-light-pollution.

Dung Beetles: In the Gutter, Gazing at the Stars | Knowable Magazine. https://knowablemagazine.org/content/article/living-world/2020/dung-beetles-gutter-gazing-stars. Accessed 20 June 2025.